|

|

Cathedrale Notre-Dame de

Chartres, located in Chartres,

France.

Chartres is considered one of the finest examples of the French

High Gothic style. The current cathedral, mostly constructed between

1193 and 1250, is one of at least five structures that have occupied the site since

the 4th century.

|

Labyrinth at Chartres

Labyrinth designs appear on pottery, baskets, on wall of caves, and in

churches. Many labyrinths set in floors or on the ground are large enough that

the path to the center and back can be walked. Historically labyrinths have

been used both in group ritual and for private meditation. One of the most

famous labyrinths is on the floor of Chartres cathedral. The original function

of the Chartres labyrinth is still debated, but the evidence does indicate, at

least, a tentative conclusion.

|

The labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral. Early 13th century.

Approximately 42 feet across.

|

There are 112 cusps around the outer circle

(see below), and four sections or quarters in the design. If you divide 112 by

4, the answer is 28, the

days of a lunar month. This led to the belief that the labyrinth

originally served as a

calendar. If so, the four sections represent the four season and provided a means of keeping track of the lunar cycles of 28

days between new moons.

With such a calendar the church could determine the very important date of Easter

and other movable feast

days.

The First Council of Nicaea

(325) established the date of Easter as the first Sunday after the full moon

(the Paschal Full Moon) following the northern hemisphere's

vernal equinox. Ecclesiastically, the

equinox is reckoned to be on March 21 (even though the equinox occurs,

astronomically speaking, on March 20 in most years), and the "Full Moon" is not

necessarily the astronomically correct date. The date of Easter therefore varies

between March 22 and April 25. Eastern Christianity bases its calculations on

the Julian Calendar whose March 21 corresponds, during the 21st century, to the

3rd of April in the Gregorian Calendar, in which calendar their celebration of

Easter therefore varies between April 4 and May 8.

There are actually 29.5306 days

between consecutive new moons, not 28, and the mediaeval scholars and clerics

were well aware of this awkward number. They created complex lunar calendrical

systems with alternating months of 29 and 30 days, with additional intercalated months

and inserted leap days, to keep the

theoretical lunar cycle in sequence with the solar calendar. This system

was devised by Dionysius Exiguus,*

a Sythian monk, during the early 6th century AD. His tables determine in advance the date

of the first full moon that would occur on or after the spring equinox in any

given year, and thus calculate the date of Easter, the primary festival of the

Christian Church.

|

| There are 112 cusps around the halo of the labyrinth. |

I

n

medieval Christian manuscripts these tables were sometimes accompanied by

drawings of labyrinths, presumably to illustrate the complexity of the subject

matter. This juxtaposition may have been influential in the subsequent

connection between labyrinths and Easter festivals and ritual dances in the

cathedrals of Italy and France. The complex alternating circuits of the

labyrinth were taken as symbolic of the intermeshing cycles of the calendars, as

well as the spheres on which the sun, moon and planets moved around the

firmament against the background of the fixed stars. Beyond these circuits lay

additional spheres representing the spiritual heavens, where saints and angels

resided. The use of labyrinths to exemplify this order demonstrates the

complex relationship of the scientific and spiritual worlds of medieval

thought.

|

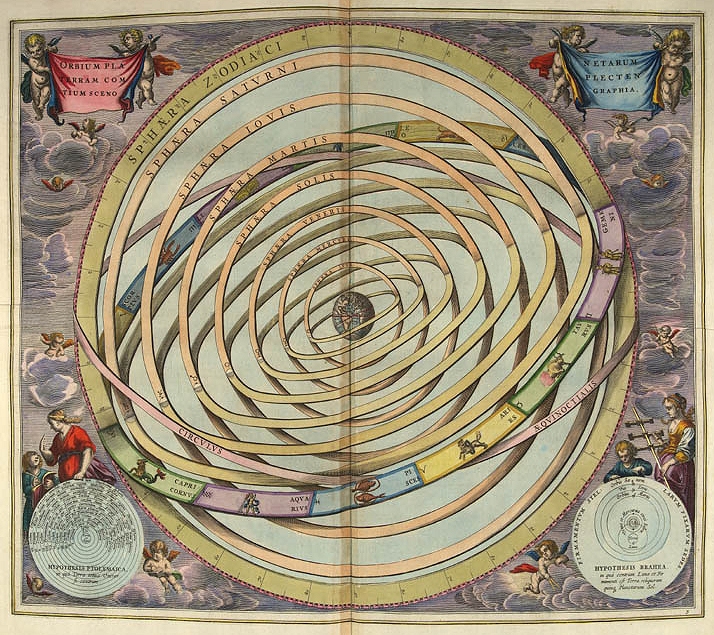

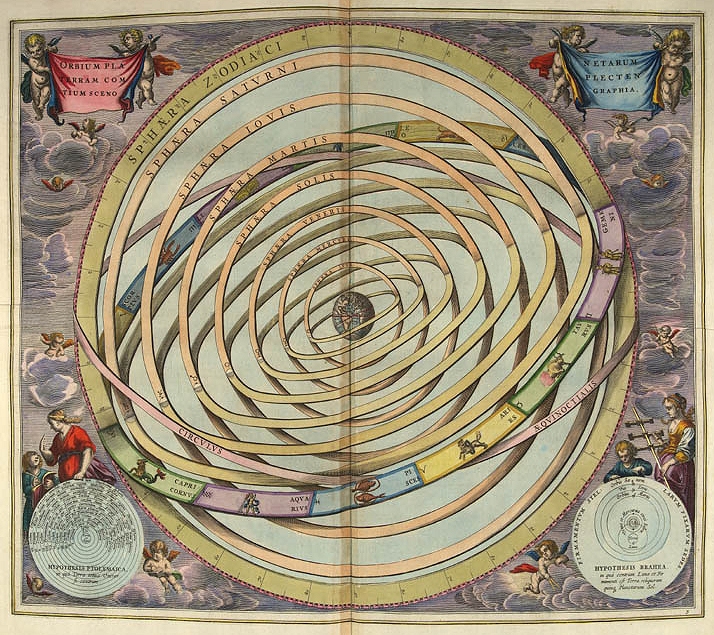

Ptolemaic Cosmos. |

Medieval man believed humans consisted of four elements, earth, water, air, and fire, which determined personality.

The right balance of these humors was necessary, to prevent one from being overtaken by passions.

Also they believed that the stars affected the balance between the humors. Thus, born under an evil star and you were cursed.

Another important belief in the medieval world view was that everything was arranged in hierarchies.

The king was at the top of the political order and the pope at the top of the religious order, on down to the farmers at the bottom. Maintaining the hierarchies preserved the world order and its relationship with the heavenly order.

Therefore everyone in society had to perform their role and cooperate in

order to make the society function smoothly. Life on earth had to be in balance with the heavenly order; this order began anew at Easter.

Church officials

at Chartres could located Easter on the labyrinth, then mark other dates of the

church calendar: for example, Ash Wednesday (46 days before Easter) and

Pentecost (49 days after Easter). So anyone around Chartres could check this

public calendar at the cathedral and prepare for a particular feast day, just as

today we check our personal desk calendars for holidays.

Religious rituals maintained the cultural order, keeping the relationship

between earth and heaven properly functioning throughout Christendom.

Their Goecentric or Ptolemaic

model held that the Earth is the center of the universe, and that all other

objects orbit around it. This geocentric model served as the predominant

cosmological system in the west beginning with the ancient Greeks. Two commonly

made observations supported the idea that the Earth was the center of the

Universe.

1) The

stars, sun, and planets appear to revolve around the Earth each day, making the

Earth the center of that system. Stars are on a celestial sphere that rotated

each day, using a line through the north and South pole as an axis.

2) The

second common sense notion supporting the geocentric model was that the Earth

does not seem to move from the perspective of an observer on Earth. Aristotle,

assuming a reasonable universe, said the Earth did not move because it had no

reason to move.

This geocentric system was challenged by Galileo's championing of

Heliocentrism. He met with opposition from astronomers, who doubted

Heliocentrism due to the absence of an observed

stellar parallax. The matter was

investigated by the Roman Inquisition in 1615, and they concluded Heliocentrism could only be supported as a possibility, not as an established

fact.

Pope Urban VIII, a personal

supporter of Galileo, asked him to give arguments for and against Heliocentrism in his

next book, and to be careful not to advocate Heliocentrism. He made another

request, that his own views on the matter be included in Galileo's book. Only

the latter of those requests was fulfilled by Galileo. Whether unknowingly or

deliberately, Simplicio, the defender of the Aristotelian Geocentric view in

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, came across as a fool. The

name "Simplicio" in Italian has the

connotation of simpleton. Galileo

put the words of Urban VIII into the mouth of Simplicio.

The Pope was outraged. Galileo had alienated his biggest and most

powerful supporter. Now Galileo was forced to face the

Jesuits and the Inquisition alone. He was tried by the Inquisition, forced to recant, and spent the rest of his life under house

arrest. All books on Heliocentrism were banned.

Part of the reason the Roman church officials opposed Galileo's system was their correctly

perceived threat to the established medieval system outlined above.** The human drama of an ordered alignment of earth with heaven

would eventually be replaced with a

scientific yet meaningless universe of black holes and dark matter we live in

today. Put another way, Thomas Aquinas and his world of system and order was

replaced by Hamlet and his disconnected world of doubt and uncertainty.

Note: The Inquisition's ban on Galileo's works was lifted in 1718, except for the condemned Dialogue. In 1758 the general prohibition against

works advocating Heliocentrism was removed from the Index of Prohibited Books, although the ban on uncensored versions of the

Dialogue and Copernicus's De Revolutionibus remained in effect.

Finally, all official opposition to Heliocentrism by the church was dropped in

1835 when these works were removed from the Index.

* Dionysius was the first known medieval Latin writer to use a precursor of

the number zero. The Latin word non or nulla meaning no/none was

used because there was no Roman number for zero.

** The Jesuits objected to Galileo's contention that the moon is a flawed

object. Heavenly bodies were taken to be perfect, i.e. "heavenly". Galileo

wrote, if the moon is in a heavenly sphere and its light shines on the pales of

my garden fence, does that not make my fence heavenly? Placing earth in a

heavenly sphere and bringing heaven down to earth upset the medieval cosmos; not

to mention the Jesuits. The best piece covering this topic is

"Moon Man" by Adam Gopnik

that appeared in the New Yorker.